Designing for Community During a Global Pandemic

A reflection on leading a remote design studio for the Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design (CIID) in Costa Rica

How can we continue to study our streets, talk to people, and test prototypes during a public health crisis? How can we identify opportunities to design for more inclusion, equity, and even joy in the everyday life of our cities? And how can we share these new research and design methods with others?

Last month, the Openbox design team had the opportunity to lead a one-week studio course for CIID’s Interaction Design Programme in San José, Costa Rica. It coincided with the moment that COVID-19 cases surged across the country and CIID’s facilities, including the maker space, digital lab, and biological research station, were closed to students. Students now worked together remotely, or masked and physically distanced in person. As the Openbox team was also working remotely in various parts of New York, Marquise Stillwell, Amy Wang, Vinay Kumar Mysore, and I used a combination of Zoom, Slack, Miro, and Notion to convene 27 designers from around the world on the topic of designing for community.

Working within these constraints and a tight turnaround time, we sketched a rough plan for students to begin the studio by using a research method we felt confident they could carry out during quarantine — to go for walks in their neighborhoods. We invited the students to form small groups and to spend time exploring familiar streets from a new perspective. The assignment was to identify, research, and prototype a space in the city that could be redesigned to better serve the community. While the students’ research and final creative outputs were very impressive, even more important to the success of the studio was the experience of adapting in real-time to changing conditions, both internal and external. As the week progressed, our team realized that our studio was not just about community design, but was also about becoming a community of support to each other and our larger surroundings during this difficult time. We’re excited to share a few key takeaways from leading an immersive design studio during this current crisis.

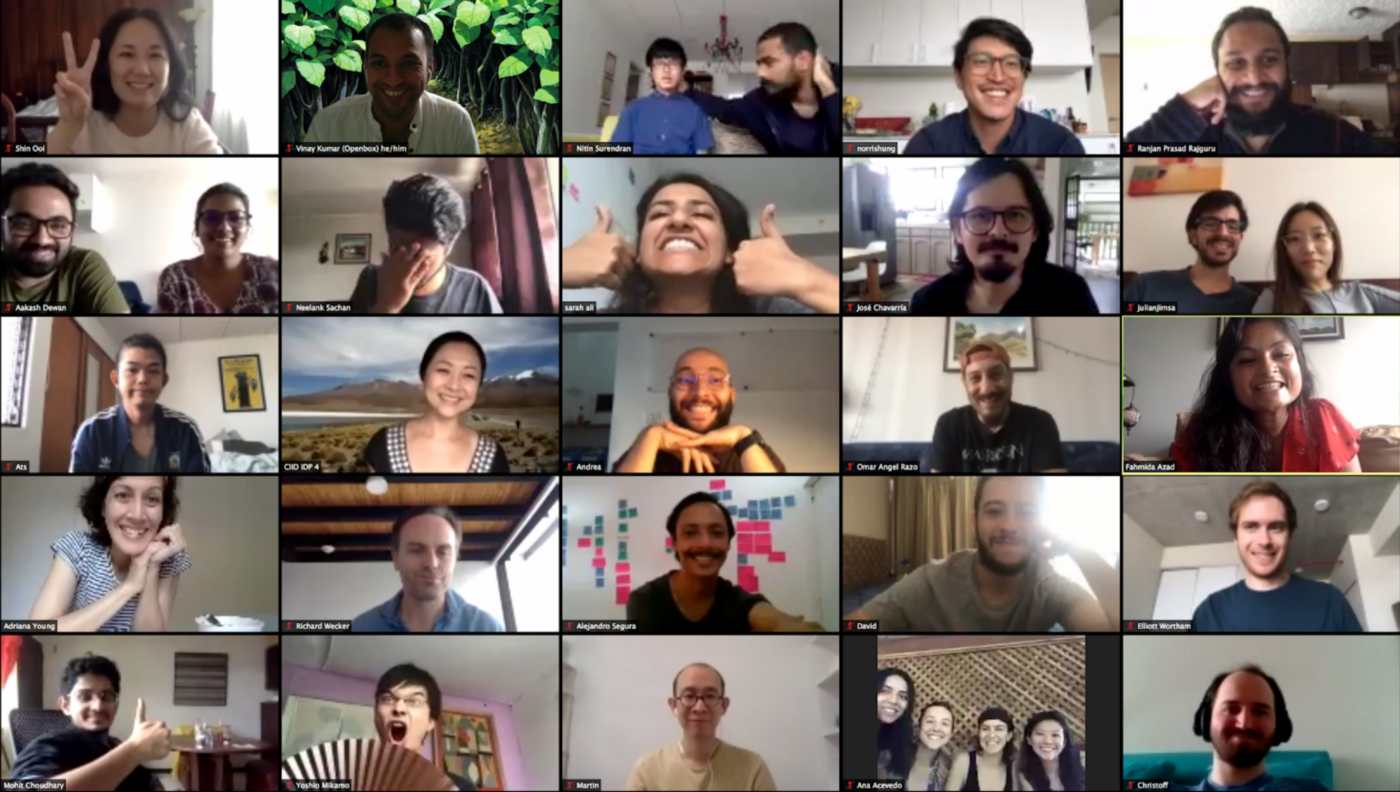

A sense of shared joy and relief at the conclusion of our intense week together.

A sense of shared joy and relief at the conclusion of our intense week together.

1. Take care of people, not just the plan.

Starting the studio with a seemingly simple exercise to walk the city proved both fruitful and frightful. Many were grateful for the chance to explore their new city by foot and discover the unique extremes of San Jose’s public life: from the irrepressible abundance of plant life brimming from even the drain pipes to gaping, unmarked potholes in the sidewalks and roads that endangered people, wildlife, and cars. Rather than explore theoretical, distant, or very technical design challenges, the students enjoyed being able to make the everyday streets the subject of their studio. While being outside and away from screens was refreshing to some students, others expressed the preference to stay indoors and explored open data sets and video walks from other cities.

Throughout the week, the regular walks and outdoor time proved both a welcome reprieve from the isolation, as well as a lesson in using moments of crisis to see dynamics that may otherwise go unnoticed. At first, teams observed empty parking lots, taped-off parks, long queues at banks, and emboldened pedestrians in the absence of heavy car traffic. They also saw how ordinary life persisted, evidenced by kids playing hopscotch while a relative looked on from a balcony and a family eating lunch outside in a small park that had yet to be taped off. By mid-week, they were digging into complex challenges such as how homeless communities would be able to safely access donated or discarded food and how otherwise mundane activities, like taking out the trash, could become a medium for social exchange. While our team shared concrete urban design research tools and provided a research or design prompt each day, we also emphasized the importance of open exploration over rigid expectations. Rather than map out specific steps where every team should be by the end of each day, we remained responsive to the students’ unexpected discoveries and blockers and focused our energies on guiding each team’s distinct journey.

Ana Acevedo, Diana Pang, Majo Tamayo, and Sammy Creeger reimagined everyday urban spaces, such as parking lots and public parks, as spaces for small community gardens where people might be able to spend time together safely.

2. Make the screen the studio.

We began each day sharing a provocative case study from a different city — from Kuwait City to San Juan, Puerto Rico — to present particular challenges to creating a research and design process anchored in community needs and perspectives. While the gathering space for learning was mostly our screens, we made the way we shared content and engaged in dialogue much more multi-dimensional. I gave my lectures appropriate soundtracks, for example playing Animal Crossing in the background as I shared principles for designing pedestrian-centered streets, and Plantasia as I talked about migrant labor rights in the style of a science fiction tale. For Amy’s lecture on designing community-centered messaging on the Zika virus, she asked everyone to remain unmuted so that we could hear each other’s breathing, sneezes, and laughs. She also did something seemingly trivial: each time students asked questions, she stopped sharing her screen so that we could all look at each other and in this way, single questions sparked in-depth discussions. Vinay facilitated a series of mostly silent, rapid-fire brainstorms on Miro and Slack, where students identified “insider” design or research jargon that should be avoided when engaging community members and practiced drafting outreach messages to recruit research participants. Each of us found our own ways of making screen time more spontaneous, theatrical, and immersive — kind of like the magic of being in a studio together.

3. Don’t forget the joy.

At the same time that students were sorting out stressful matters like debating to travel back to their home countries and figuring out how to safely collaborate in person, our team intentionally made space for play. While the main case studies we shared were heavy on uncertainty, messiness, and extraordinary political and social constraints, we also peppered in whimsical examples of tactical urbanism and a field trip to a kid-created, virtual city.

We spent time with the artist Kay Liang in the wild and magical world of Tiny Town, which she created with eight kids when the pandemic first unfolded in the spring. Composed of not much more than a simple urban plan, a mysterious rule that all children must stay home, and weekly drawings and role playing from the kids, our students experienced how Kay’s game created a place where kids could partake in both the serious and silly social interactions they craved — from escaping to a hidden beach to listening to a famous band of singing dogs. Our visit inspired some of the teams to add elements of storytelling and delight to their design interventions, which we can be especially powerful means of engagement in moments of crisis.

Overall, as a team of design practitioners and educators, teaching this studio refreshed our sense of collective purpose and play. While we remain committed to identifying and fixing the many broken systems that have left our cities and communities more vulnerable in this crisis, we found that the chance to teach and connect with emergent designers from around the world made us feel less overwhelmed by the task at hand and instead, more energized by the amazing potential we see around us.

= = =

Many thanks to the CIID Costa Rica students and staff :)